What Are You Trying to Learn?

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

—Albert Einstein

What Are You Trying to Learn?

In school, we’re constantly taking tests to gauge how well we learned last week’s material. We cram geographic boundaries, the dates of battles, and multiplication tables into our heads, and then we spit out the results.

Sadly, those rote memorization skills used to answer preformulated questions don’t help us as entrepreneurs. When building a new business model, there is no test or quiz that we can cram for. It’s as if we sat down for our final exam and opened up the book only to find a blank piece of paper in front of us.

“Where is the test?” we ask.

“Right there in front of you,” answers our teacher.

“Is there a right answer?” we hesitantly inquire.

“Yes there is,” assures our teacher.

“What are the questions?” we plead.

“That’s what you have to figure out.”

As an entrepreneur (or intrapreneur), we can’t just guess at the answers without first identifying the right questions. If we guess by building a fully functioning product, it’s likely that the market will judge us wrong and punish us with zero sales and eventual bankruptcy.

Our job as entrepreneurs is to first ask the right questions, and only then can we find the right answers.

What Are Good Questions?

The questions we must answer are fundamental gaps in our business model. Questions like:

- Who is our customer?

- What job do they want done?

- What channels can we use to reach them?

- Which features should we build for our first product?

- Is our solution good enough?

If we can identify the right question, there is a corresponding method (or methods) in this book to help answer it.

If we apply a method without first identifying the right question, the results of that experiment are typically very difficult — if not impossible — to correctly interpret.

For example, let’s say we’re selling a new type of shoe that cures plantar fasciitis. We put up a landing page test (a type of smoke test) with our value proposition and a “Buy Now” button. Then we put $1000 into Google AdWords for “shoes” to drive traffic and wait for the money to start rolling in.

Later, it turns out that our conversion rate is 0 percent.

Should we give up? The landing page test says that there is insufficient demand for this product.

“But what is plantar fasciitis?”

It turns out that everyone coming to our site has been asking this question.

Is our test failing because customers aren’t interested, or is it simply because our customers can’t understand the value proposition? Or are we focused on the wrong channel?

In this case, we were asking, “Does anyone want my product?” when we should have been asking, “Does our customer understand what plantar fasciitis is?” or even, “Who is our customer?”

How Do We Ask the Right Questions?

Asking the right questions is important, but actually figuring out those questions can be a challenge. How do we know we’re not missing anything? How do we know we are asking the most important questions?

It’s impossible to see our own blind spots. (That's actually the definition of a blind spot.)

Unfortunately, it’s often these blind spots that hold the deadliest questions and business risks.

One way to generate these questions is brainstorming around problems/challenges/opportunities and reframing them as questions. There are many ways to brainstorm questions and identify gaps in our business model, such as using the Business Model Canvas, but most of them still leave blind spots. Fortunately, it’s easy for other people who have a little emotional distance from our business to see where we are making risky assumptions. So instead of listing a variety of brainstorming methods, the only advice we’ll offer in this book is to ask someone else.

A peer review is a time-honored method of eliminating oversights. It can be used to proofread a document or make sure we’re not about to walk out of the house with mismatched socks.

To peer review our business model, we don’t need to ask a seasoned entrepreneur or industry expert. Almost anyone is able to provide the input we need.

We can present our business idea and business model to someone else and ask them to ask us questions. Encourage them to ask any question they want, and remind them that there are no dumb questions.

We simply need to write down those questions that we forgot to ask ourselves. If we go through five peer reviews and everyone asks us, “Who is your target customer?” or says “Gee … your target customer seems broad,” we probably haven’t defined our target customer very well.

We should not defend our idea or try to explain in excruciating detail why their question is not a risk for us. Our job is only to note the questions that are being asked and include them when we prioritize.

Priority Does Not Have a Plural

Once we’ve finished brainstorming and conducting peer reviews, we should have at least ten questions, and hopefully much more. If you have fewer than ten, you are probably missing questions in your blind spots.

Startups are risky. There are a lot of unknowns and a lot of open questions. If we can only see five or six questions, it does not mean our startup is less risky than someone with twenty questions. It actually means our startup is more risky because we are not acknowledging and dealing with those unknowns.

However, we can only address one question at a time effectively. So we have to prioritize.

Again, there are many methods for prioritizing, and we won’t list them all here. We should just pick one question where the answer could potentially destroy our entire business model.

We may choose the wrong question to start with. That’s ok.

It's better to pick the wrong question and answer it quickly than to spend days, weeks, or months agonizing over multiple priorities to develop a perfect plan of action for the next year. Just pick one and get going.

The following sections will show you how to take that one priority question and figure out how to answer it with research or an experiment.

Locate the Question

To simplify our search for the right method, we’ll ask two questions:

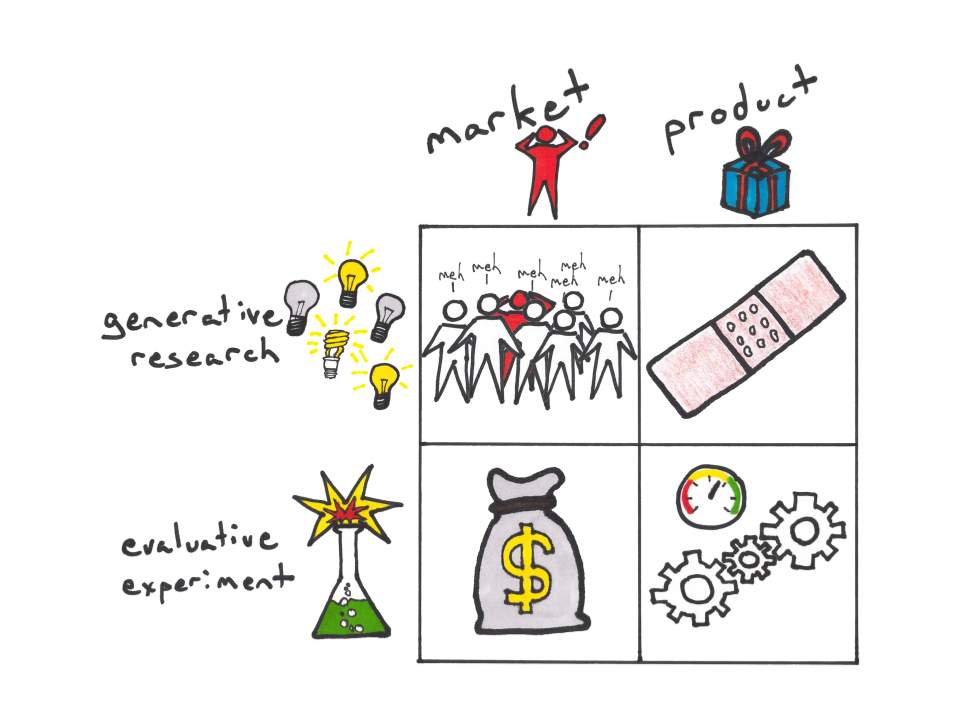

- Do we need to learn about the problem (ie, market) or the solution (ie, product)?

- Do we have a falsifiable hypothesis to evaluate, or do we need to generate a clear idea?

Mapping the intersection of these two questions gives us a 2x2 matrix:

Based on this, if we have a clear hypothesis of who our customer is and what we think they will pay for, we can conduct an Evaluative Market Experiment such as a smoke test.

If we don’t have a clear idea of who our customer is, we can do Generative Market Research, such as data mining.

Similarly, if we have a clear hypothesis of which features will solve the customer’s problems, we can do an Evaluative Product Experiment such as Wizard of Oz testing. If we do not know which features will lead to an acceptable solution, we can do Generative Product Research such as a Concierge Product to try to come up with new ideas.

Any framework is an oversimplification of reality, but this index is a quick way to navigate to the correct method.

The Index of Questions and the Index of Methods show the complete list of questions and their corresponding methods. But first we’ll look at the details of problem vs. solution, and generative research vs. evaluative experiment.