Every few weeks, someone asks us if there’s a lean startup template that they should use to define their experiments…and we say no.

We’re not big fans of templates in the broad sense of a ‘one size fits all’ approach to define experiments regardless of the context.

We ARE huge fans of having a repeatable process.

We (Kromatic) do use templates that work well for us. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll work well for someone else.

Templates are often a means of asserting order over the innovation process in order to measure team velocity in an overly stringent way before it’s appropriate or necessary to do so.

So in an effort to satisfy the requests and not give overly broad advice, here’s the template we use and why we designed it this way.

If you’d like to cut to the chase, you can download the template below. It’s licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License so feel free to modify and hack to make your own.

Download Learn S.M.A.R.T. Template

The Basics

Any template, framework, or checklist is there to provide us with a repeatable process. A lean startup template should provoke us to think harder, not remove the need for critical thought.

It should remind us of important points to consider and frame the question in a way that makes sense.

The basic criteria for a lean startup experiment is always:

- Hypothesis

- Metric

- Experiment

Most templates such as Ash Maurya’s & The Validation Board have these elements. This is a great place to start when we define our own template. Just this and no more.

Run a few experiments, did we learn from them? Is the team in agreement on the results? If yes…that’s all we need.

If we find there is some disagreement as to how to interpret the results, such as: the experiment lasted longer than it should have or we’re not learning the things that are critical to our business, then it’s time to modify the template.

Hypothesis

The hypothesis is what we’re testing. It must be a clear statement that is falsifiable.

It should also be something that is risky.

A good experiment will generate an invalid hypothesis about half the time.

If our hypotheses are always valid, then we're not testing risky assumptions. Click To TweetOur hypothesis might be about our customer, our channels, even our key resources. We can use the Business Model Canvas or other tools to help identify a hypothesis. Some good examples:

- Bernie, our customer persona, has foot pain because of running for exercise three days a week.

- If we add logos of our existing customers to our landing page, it will convey trust as a key value proposition to Bernie, our customer persona, and he will sign up.

- Potential partners will fill out a lead sheet when they view a partner page explaining our three key value propositions.

Hypotheses should be clear statements that indicate a causal relationship with a clear actor (i.e. customer). Some bad examples:

- Some people will sign up if we launch this landing page.

This is almost certainly true. Somebody always signs up for every landing page.

- We believe consumers will enjoy this feature.

Firstly, we’re supposed to be testing reality, not trying to test our beliefs. (Do you think users will enjoy this feature? Yes. Hypothesis validated!)

Secondly, “consumers” is vague. Which consumers? Will my 80-year-old grandmother use it? Be specific.

Thirdly, we can only test things that are observable. I can’t test whether two magnets dislike each other. I can test if they will physically move away from one another.

Make your hypothesis strong and the rest of the experiment will write itself.

Metric

The metric is what we will measure in order to invalidate that hypothesis. That data can be quantitative or, in some cases, qualitative.

Plenty has been written about this subject elsewhere, so just make sure it’s not a vanity metric such as “number of likes.” (Also see, “Failure Condition” below.)

Plan

The plan is a clear description of the steps we must take to gather that data.

Sometimes this might include wireframes or interview scripts. We only put in enough information such that everyone agrees that they could execute the experiment without further questions.

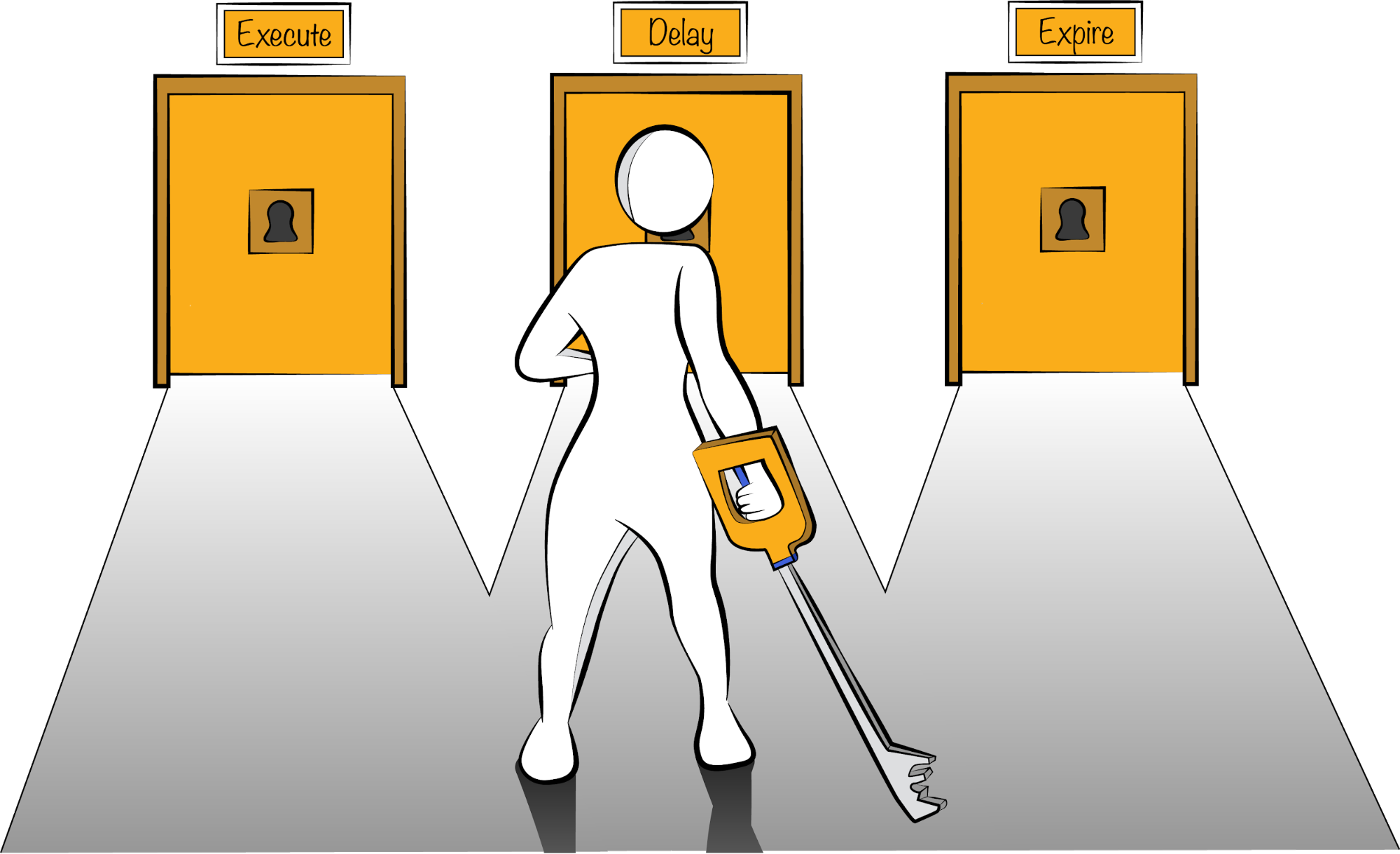

Hacking the Lean Startup Template

Unfortunately, sometimes the simple template isn’t sufficient and we find ourselves in the infamous “Build-Measure-Flail” loop.

Don’t panic! Do a retro, then modify your template so that situation doesn’t occur again.

Learning Goal

We’ve found that occasionally we run experiments which don’t seem to have a clear purpose, or are tangential to our critical business decisions. Sometimes things just sneak in as pet projects. Sometimes we just thought they were important and looking back it seems that the share button on our blog wasn’t really that critical.

We’ve found that occasionally we run experiments which don’t seem to have a clear purpose, or are tangential to our critical business decisions. Sometimes things just sneak in as pet projects. Sometimes we just thought they were important and looking back it seems that the share button on our blog wasn’t really that critical.

To counter this, we add a Learning Goal to our template. The learning goal is broader than a hypothesis. If you’re familiar with Agile, you can think of this as the epic. Typical learning goals might be:

- Does Sally, our customer persona, need help getting through her homework assignments?

- Is LinkedIn Advertising a good channel to reach Sally?

- Will adding an option to video chat with a tutor make sally use our product more?

These things are not specific enough to be hypotheses. They are not falsifiable. They are very broad and are likely to be big questions which have a number of possible answers, each of which we can test in succession.

This field is useful so that we always remember to tie our experiments back to a critical component of our business such as the business model canvas. Many other templates have a similar component, some even use the Business Model Canvas as the Learning goal.

Fail Condition

Generally we’re pretty good at setting metrics for our experiments, but we occasionally get a result and don’t know

what to do with it.

Is 7.6% conversion rate on that landing page good or bad? If we don’t know, then the outcome of this experiment isn’t going to help us decide what to do next.

The Fail Condition is the resulting measurement which would convince us beyond any reasonable doubt that our hypothesis is invalid.

This is more useful to us than success criteria because we tend to be overly lenient in success criteria. If we consider success to be a 50% conversion…49% will do just fine.

45% isn’t too bad either.

We can probably optimize 30%.

15%? Well…maybe we hit the wrong target market or maybe we should wait until the school year starts.

By setting a fail condition, we are acknowledging a basic tenant of science:

You can never prove a hypothesis, but you can always disprove it. Click To TweetIf we can’t agree on a fail condition, our hypothesis is not falsifiable and our test is meaningless.

If our fail condition is <10% conversion rate…then a 9.999% conversion rate is still a fail and we are forced to acknowledge that.

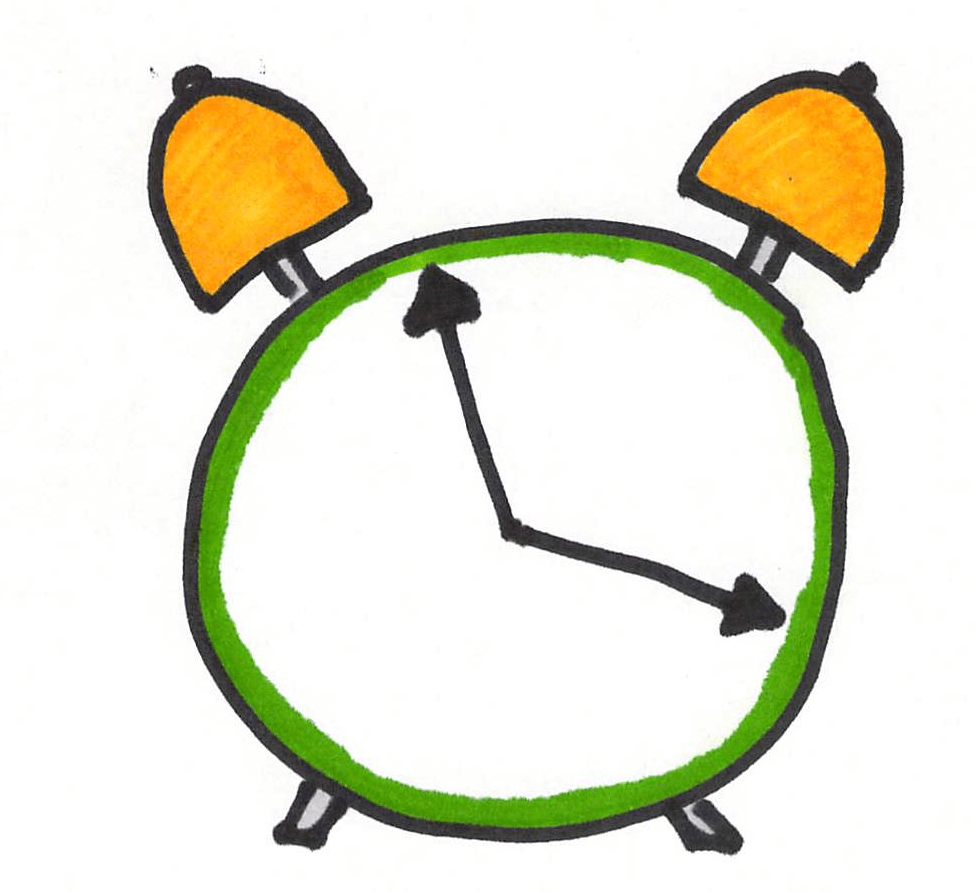

Time Box

It’s important for us to constrain the amount of time the experiment will run to keep us moving fast.

It’s important for us to constrain the amount of time the experiment will run to keep us moving fast.

If we argue that in order to gather sufficient data for a statistically significant sample size we will have to run the experiment for four weeks, then we should probably define a hypothesis we can test in a shorter time, a better metric, or start cheating or hacking our way to a larger sample size however we can.

Agile practices also use time boxes, often in the form of a set sprint length. It helps constrain feature creep.

If the experiment will last longer than a week, we are probably not being aggressive enough.

There is always a way to invalidate the hypothesis within a week. Always. Click To TweetResults

Any experiment template really ought to have a results box.

Any experiment template really ought to have a results box.

Some people may be able to remember everything with crystal clear precision. We cannot.

We always want to be able to look up what we did six months ago if that data becomes relevant in another context.

If we’re not getting results, we’re obviously not learning.

Next Step

Similarly, if the results of the experiment don’t inform what our next steps should be, something went wrong with our experiment. At the very least, the experiment should tell us, “Don’t do that again.”

Similarly, if the results of the experiment don’t inform what our next steps should be, something went wrong with our experiment. At the very least, the experiment should tell us, “Don’t do that again.”

Preferably, the results should suggest the next experiment to perform which may be based on the same epic, may be a higher fidelity test of the same hypothesis, or it might indicate that the hypothesis is now “less risky” and it’s time to investigate another element of our business model.

If no clear step is apparent, it’s a warning sign that we may have been experimenting on something irrelevant or low priority.

WTF,s!

Credit for this goes to Kenny Nguyen although we’ve seen a few teams implement something similar. WTF,s! stands for “What the fuck, stop!”

Something has gone fundamentally wrong with our experiment and it’s time to turn it off early and retro.

This is our opportunity to look for additional elements to minimize the experiment and find smaller ways of getting valid data.

For example, if we are testing the sign-up rate on a landing page and we’re going to drive 1,000 visitors to the landing page via our newsletter, we could set a wtf,s! condition as “If the open rate on our newsletter is <50% with the first 100 sends…wtf,s!”

Since our benchmark for other newsletters is 60%, did we fail to install tracking? Is the subject line utterly horrible? We might only have 2,000 people on our mailing list, and sending too many emails to the same list will burn out the list. It’s a limited resource. So let’s send out our email in small batches and make sure we haven’t done something dumb.

Some dumb things I’ve personally done:

- 0% conversion? Ooops…broke the analytics by deploying a small change straight to production.

- Sent a templated email with a subject line for a workshop that tested really well on Twitter but is marginally offensive via email. (Sorry to everyone I told “Your MVP sucks!”)

- Forgot to turn adwords off.

BYOT – Bring Your Own Template

If this template works for you, great. Go for it. We use it for both doing research and running experiments:

Download Learn S.M.A.R.T. Template

If another one works better, great!

Better yet, it’s licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License so feel free to modify and hack it to make your own.

But please please please do not force your hapless startups or innovation teams to use an arbitrary template just so you can measure how fast they are innovating. It makes us cry.

Make better product and business decisions with actionable data

Gain confidence that you're running the right kind of tests in a five-week series of live sessions and online exercises with our Running Better Experiments program. Refine your experiment process to reduce bias, uncover actionable results, and define clear next steps.

Reserve a seat